What did you learn tonight?

You're shouting so loud

You barely joyous, broken thing

You're a voice that never sings, is what I say

-The Archers Bows Have Broken, Brand New

The trouble started shortly after I bought my truck.

Out of an abundance of caution, I would park halfway off the driveway to give my wife ample room to pull in and out of the garage. She probably only needed an extra foot, but being thoughtful (paranoid), I gave her more than that. A small, growing pool of water appeared underneath my tire in less than a week.

I turned to my stepdad for help. When it comes to home repair, he knows everything. He noticed the leak sprung up near the water meter, which likely meant the main water line to the house was damaged. If I dug up the pipe, he’d help me fix it.

Standard residential water lines are buried about a foot deep and laid in a relatively straight line up to the house. Given that, it should be a quick project digging out the pipe on the left side of the meter.

One problem, though. The leak was on the right side of the water meter. Why would the water be pooling almost six feet away from the pipe?

“Dig where the water line is,” he responded. “If you start by the driveway, you won’t find anything but dirt.”

Fair enough. After an hour under the August sun, I had dug a three-foot-deep and two-foot-wide hole. No pipes. No water. No way this was possible.

What the hell?

Finally, mercifully, my wife suggested I start over and dig where the water was. I tried to explain to her that nothing would be there - nobody would bury a water line next to the driveway. I didn’t want to keep digging useless holes in the ground, but I eventually relented and resigned to doing just that to show her how wrong she was.

Less than five minutes of digging, boom, water line (sorry, honey). It was exactly where you’d expect…if you knew nothing about how residential water lines were set up.

What, and I mean this with all sincerity, the hell?

Copper is the standard for water lines and is also pretty expensive. What likely happened was an entrepreneurial installer made it look like copper was being used but, at the last minute (or shortly thereafter), swapped in cheap PVC. They went so far as to use copper fittings at the water meter (where the inspectors could see it), but as the pipes went into the ground, they switched to PVC and went around the water meter to disguise the ruse. They half-assed it, leaving it higher in the ground than you’d typically install it, which is how my truck ultimately put a crack into it when I parked on the side of the driveway.

In my stepdad’s defense, this was a pretty unique case. In normal circumstances, his advice would have been spot-on. But in this case, his expertise misled him. It blinded him, even. What was objectively true was incompatible with what he knew to be true.

Sometimes, we’re oblivious to what’s obvious.

Sometimes, we discount what we see to sustain what we believe.

Sometimes, we have to dig where the water is.

History is replete with examples of being oblivious to the obvious. The concept of a spherical Earth wasn’t well-established in educated circles until the mid-16th century despite supporting evidence provided as far back as the 6th century BCE! Ancient Greeks, Indians, and Islamic scholars independently accurately estimated the circumference of the Earth long before Christopher Columbus sailed to the Americas.

Why does this happen? A few thoughts:

We’re seduced by stories, so a compelling narrative can override the facts it’s built upon.

We settle for shared wisdom because it’s easier than judging each situation as novel.

We seek safety, and there’s nothing safer than deferring to an expert.

All three played a role in my hole-y crusade (sorry) above, but the third bullet is one that I find particularly interesting.

Why do we defer to experts, even when what they say doesn’t align with what we see?

Shortcuts

To grow, we have to learn. To learn, we have to experience.

Most of the time, those experiences teach us what not to do. So, we could simplify here and say to grow, one must experience failure.

But experiencing failure doesn’t mean you have to fail. You could experience it by proxy. You could research, observe, or inquire such that other’s failures teach you what not to do from a safe distance.

Thus, the simplistic model of learning consists of two paths:

Learn from your screw-ups.

Learn from others’ screw-ups.

Given the choice, the latter feels obvious. We’re predisposed to avoid pain, so we generally welcome advice from those who know better. We seek the input of experts so that we, too, can make expert-level decisions without the cost of acquiring expert-level instincts firsthand.

Path 2 is a shortcut.

But, as I said, this framework is simplistic. There are two paths, but distinguishing which is which isn’t always obvious.

Whether to defer to others’ expertise requires us to make a series of judgments:

Are they experts?

Is their track record of good outcomes easily attributable to decision quality (versus luck)?

Is their expertise applicable to this situation?

Often, we shortcut this process by deferring to our intuition (System 1), substituting hard questions like the above for simple ones like “Is this person in a position of expertise?” or “Is this person successful?” or “Do I trust them?” Sometimes, it works in our favor, and sometimes, you’re digging a hole in the middle of your yard like a wayward puppy.

Further, when we rely on others, we tend to remove our judgment from the equation entirely. In a perfect world, we would judge what we’re being told based on what we know and observe, thereby using the expertise as an input into our decision-making rather than a substitute for it.

This is a position companies find themselves in all the time. Faced with a challenge, they hire consultants to provide expertise and guide decision-making to avoid the pains of Path 1. Unfortunately, the expertise doesn’t always pan out, like what happened when AT&T engaged McKinsey in 1980 to estimate the cell phone market by 2000:

The consulting giant said that it would be “niche” with a size of 900,000 subscribers.

The recommendation was for AT&T not do cellular. Mckinsey was obviously very wrong. In 2000, about 900,000 cell phone subs joined every day (and the market was well over 100 million users).

AT&T paid for the mistake: in 1993, it spent $12.6B to acquire McCaw Cellular (the 5th largest ever US corporate acquisition at the time).

It’s easy to criticize this and other “expert” opinions, but the reality is that there’s typically sound reasoning behind the idea. Further, those seeking advice are delegating inputs into the decision but not the decision itself. What isn’t clear from the story is whether anyone at AT&T had any evidence to dispute McKinsey's assumptions. If so, the real failure here was the failure to synthesize these disparate opinions. If not, well, that’s what happens when you follow the consensus.

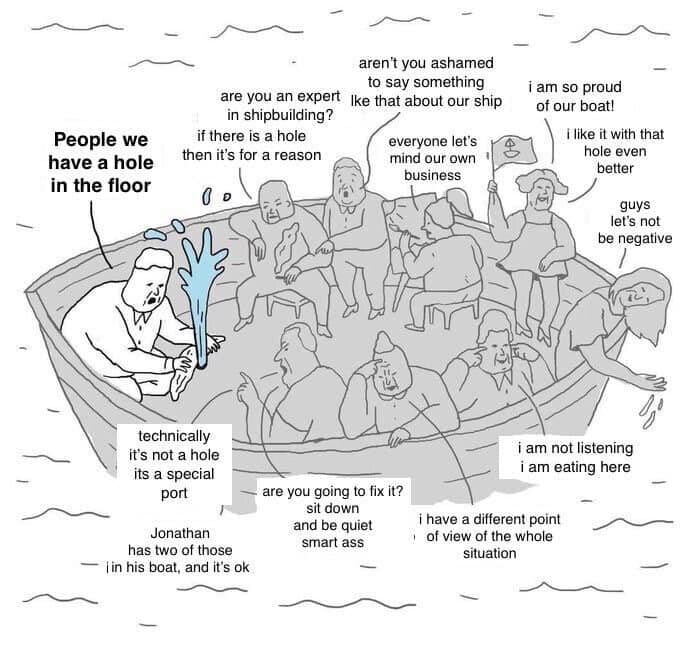

Expertise blinds us to uncommon or unusual use cases, so what works on average will fail spectacularly on the edges. We have to be careful not to conflate being wrong with being foolish. The challenge for us, the Path 2 seekers, is distinguishing what advice to take and what to avoid.

Immunization

How do we take responsibility for the expertise we leverage in our decision-making? We have to immunize ourselves to it’s second and third-order effects.

Observe. Don’t let the judgment of others blind you to what you see. Look for divergence between what you see and what’s being said.

Inquire. Relieve the tension between what you see and what you’re told by asking what could explain the disconnect.

Own. As the decision maker, you are responsible for the decision and how you decide. You can defer to others’ input and expertise but ultimately own those inputs if you rely on them. Take that ownership seriously and address concerns before the decision is made, not after.

Conclusion

I’ve learned a lot from my stepdad over the years.

He taught me that anything that breaks can be fixed, even if it means taking a microwave apart piece by piece. That any skill can be learned, even if (or especially when) it scares you. That every day is beautiful, even when it’s over 110 degrees outside.

But the most important lesson I learned from him was that you should dig where the water is, not where it should be.

Expert advice is a valuable input, but ultimately, it’s just an input. I leave you with Will Smith’s advice on how to think about advice in his autobiography, Will:

The thing I’ve learned over the years about advice is that no one can accurately predict the future, but we all think we can. So advice at its best is one person’s limited perspective of the infinite possibilities before you. People’s advice is based on their fears, their experiences, their prejudices, and at the end of the day, their advice is just that: it’s theirs, not yours.

When people give you advice, they’re basing it on what they would do, what they can perceive, on what they think you can do. But the bottom line is, while yes, it is true that we are all subject to a series of universal laws, patterns, tides, and currents—all of which are somewhat predictable—you are the first time you’ve ever happened. YOU and NOW are a unique occurrence, of which you are the most reliable measure of all the possibilities.

Consider supporting Tots Blog

Subscribing ensures you get the latest and greatest in your inbox as they come out!Subscribe now

Liking and commenting helps other folks find this publication.

Sharing it in your group chats or social media

Refer a Friend or Forward it to them

Thanks to Roman Eskue for graciously reviewing this post to help me improve it before publishing!